James Tooze is a senior tutor on the Design Products programme at the Royal College of Art (RCA). His background is as a furniture designer and maker and he now works as a researcher based at the RCA. His particular research interests combine open design, digital manufacturing, open workshops and sustainability. At Think Up we are investigating how engineers from different engineering disciplines go about their design work. We are looking for the characteristic processes and considerations that distinguish one sector from another so that we can better train engineering students in design.

The engineering of consumer products, from internet-enabled smart metres to folding bicycles, involves engineers from many different disciplines working together to create products that consumers want and will pay for. To get a greater understanding of how this consumer focus influences the design process, I interviewed James about the strategies of a product designer. The questions are loosely based around a standard set that I have been using with engineers from a range of different disciplines. (To answer the questions yourself, you can do so on our online form and contribute to our research).

What is being designed?

The students that James teaches design everything from furniture systems calibrated to a circular economy, new materials for consumer electronics, to new forms of sustainable canal housing. As James works with students who are going on to design a whole range of different types of products, his answers relate to a general approach for product design rather than the specific needs of any given product.

Establishing the brief

In response to what need?

In James’s view, product designers design in a response to a range of different factors, which can be either personal and/or driven by the project:

- Not needs based but design as an investigation – to find rich territories to explore as a designer.

- To create objects that speak about people or for people

- To understand the relationship between humans and things

- To understand how objects can become extensions of people.

- To negotiate between people and criteria.

- As enterprise: to design something that will enable the designer or client to make a profit.

An important need that underlies product design is the need to get paid. When you are designing a product, you are designing a way to get paid. And not to be overlooked is the need for enjoyment, achieved through the act of developing ideas, engaging with people and understanding how people engage with the world.

What key information does the brief give you?

The amount of information the brief gives you depends on whether you have been given the brief, or whether you have written it yourself. As James explains, there is a danger when the brief merely describes a preconceived idea that the client has already imagined rather than as a framing for a design challenge. Much better is to have a brief that gives you a set of criteria that you need to meet. What you need to look for is the criteria in the brief and not the answer.

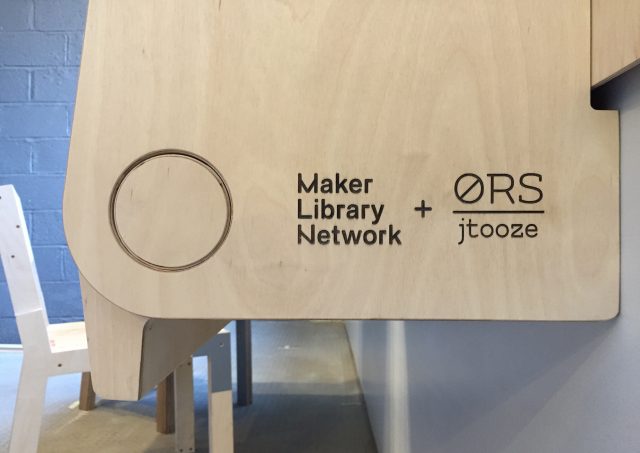

James describes the process that he went through to develop the brief for a new furniture system he designed called the Open Rail System (ORS) with Opendesk.cc. Part of the brief came from the collaborators criteria (Opendesk’s business model), part of the brief came from what ORS was intended to do (enable workspaces to be reconfigured very easily), and part of the brief came from an understanding of what technological boundaries are available to push (CNC machining of plywood).

What is usually missing from a brief that you need to go and find out?

What is often missing, says James, is an honest appraisal of what the project is trying to do, and that is what the designer needs to try and find out. This observation relates closely to the previous point about how well established the brief is when the designer first comes into contact with it. If the project is in its very early stages, it can be easier to discover what this underlying need is; when a project is more developed you are sometimes locked into design criteria or requirements that compromise the range of choices that can be made for final design.

Another point that James makes is that for designers, design is a process of learning. So the thing you are often looking for in a brief is an opportunity to explore something new, for example in the application of a new technology to a given context.

Developing ideas

Evolution or revolution?

‘We don’t design in a vacuum’ – it’s very rare that we get revolution, our ideas are mostly evolution. As James explains, even when you see something that seems like a revolutionary approach, it still has elements of pre-existing technologies. ‘What we are doing is bringing together people who know stuff and existing technologies to do new things.’

When developing a solution, what comes first?

The key thing to ask is who is this for. What you need is a deep understanding of who the product is for and everything else cascades from that. Having said that, James goes on to add it doesn’t always work like this: in practice, you just start working and discover useful things as you go.

Once you know the domain in which you are working your job is to find out as much as you can about that world. You need to be mindful of what you do and don’t know; you need to be able to communicate with experts to find out what you need to know.

You also need to be able to interact with users – they are the experts about themselves. Empathy is part of the skill set of the designer. You need to not just to find common ground, but really understand what someone engaging with the product would get out of it – not just in terms of utility but also feeling.

Are there a set of go-to answers to consider first?

The set of possible answers you might consider is determined by the answer to the question below.

Can you characterise the dominant uncertainty?

One of the key things that dominates the nature of the response to a brief is the scale of manufacture. Is what you are creating a one-off or will it be made in the millions? The answer to this question has significant consequences for the rest of the design. If you are designing for mass manufacture then you also have to design for the global logistics chain that will get your product to your market. However, as James points out, large production numbers doesn’t necessarily mean mass manufacture. The alternative is a distributed manufacturing model, where elements are manufactured and assembled local to the market or even by the user themselves.

Another factor which dominates the solution space is affordability, which can impact on every aspect of the design.

Developing and choosing ideas

What models do you use to test an idea?

James’s go-to modelling tools are hand sketches, 3D CAD, such as Solidworks or Fusion 360, and one-to-one models of components or even the full thing if possible. The full prototype can be the first version of the product (if it is highly experimental), it all depends on what you are doing.

One-to-one prototyping is fundamental in product design: it allows you to feel it, walk around it, pick it up and understand the weight distribution. As James explains, design is negotiating between the world as you imagine it and how you experience it. Until you make a model of if you can’t feel it. ‘I need to make models to know how I am going to feel about it. It is a reflective tool: it is more to show you what you haven’t thought of than to prove what you have done is right.’

What models do you use for communicating ideas with others?

For James this is totally dependent on what he is working on and for whom. You need to understand the problem, but also understand the person you are working for or with, and how they envisage the problem. Some collaborators just need an indicative sketch; others need to be told a story; others need full mock-ups.

Other key considerations are:

- Is there enough money in the project to create a full mock-up?

- Is there a risk of investing time in a model when a sketch will do?

- How much of what you are doing is new to you, and therefore, how much do you need to validate it, for yourself and for the client?

What are the most important tests that tend to determine whether or not an idea meets the brief?

Beyond basic structural testing, for James the most important type of test is user testing – really getting feedback from your perceived audience. Following on from the point above about one-to-one modelling, user testing isn’t necessarily a validation process, it is as much a chance to get feedback about what you haven’t yet thought of. Long-term in-situ testing can continue to give you really important user data which you can use to inform the next iteration of your design.

When are bad decisions made in product design?

The classic situation James describes is when the designer can’t reconcile the difference between the project needs and their own needs or aspirations as a designer. Trying to shoehorn a personal agenda into a brief can be a recipe for disaster.

To what extent are design decisions codified in product design?

There are a number of off-the-shelf design process methodologies that people use, such as in IDEO method cards, the Luma Institute’s design methods or service design tools in This is Service Design Thinking. Beyond these, there are also ergonomic, safety and performance standards that relate to whatever it is that is being designed.

What are the consequences of making a bad decision in your domain of design?

According to James, it depends on when you make it. Ideally, you should be following a fail-often-and-early design philosophy, which means the mistakes come up when they are cheap to rectify. If you have a good process, then you will recognise the flaws in your thinking before it is too late and you can adjust. Deal with bad decisions early and they are cheaper to deal with, leave it late and they can get expensive.

When carrying out design in your sector, what are the first three to five things you consider?

- Who – audience / market: their needs, contexts and diversity

- Volume of production – how many things you intend to make relates directly to production methods, logistics, market size, etc.

- Impact – what are the consequences of your design existing: to produce it, ship it, use it, and recapture the resources in it for future use. And how do you mitigate these?

- Dream – what can you conceive that would make this project / product special or magical?

Related Content

- Post: What strategies do top engineers from different sectors of industry use in design?

- Post: The Strategies of a Circular designer

- Post: Strategies of a Consumer Electronics Designer

- Post: Designing Structures That Move

- Post: Strategies of an Electronic Engineer

- Post: How to Have Ideas – Workshop Toolbox

- Post: How to have ideas today in Bath

- Post: Having ideas at the IABSE Bath 2017 conference

- Event: How to have ideas